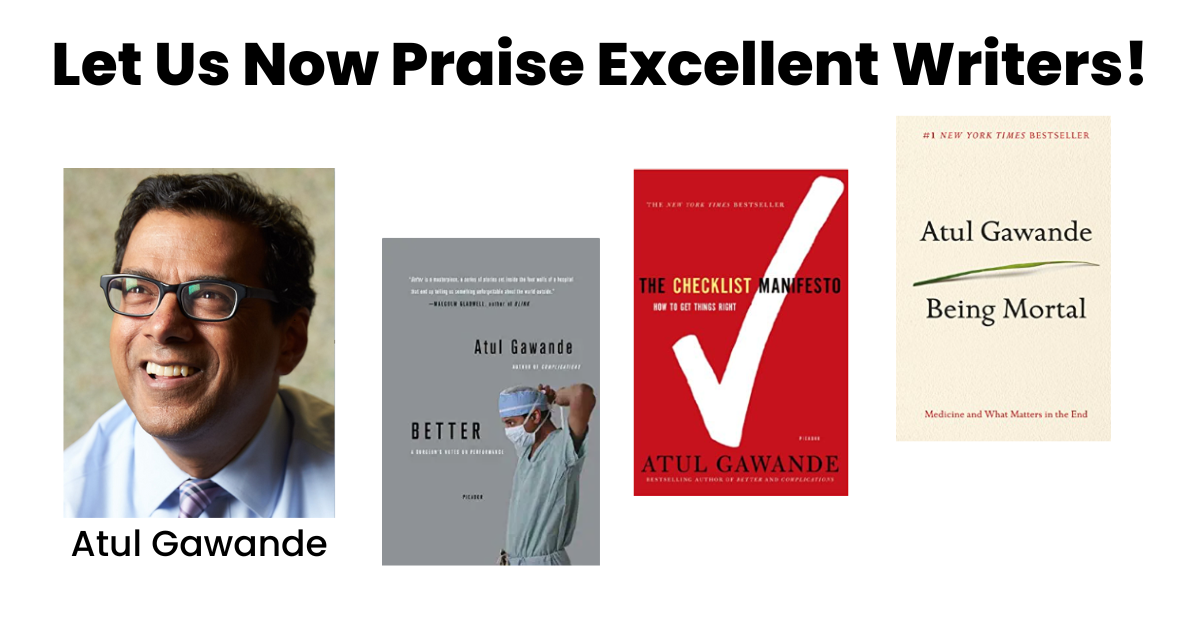

The very first experiment in Sit Write Share suggests that you improve your writing by reading excellent writing. As far as I’m concerned, any reading is good. Feel free to enjoy comic books or suspense novels. It is also wise to spend some time reading works by people who are very good at writing the kinds of materials you want to write. One of my personal models is Atul Gawande.

It is my hope to start a series in this blog that could be called, Let Us Now Praise Famous Writers. This is the first one. There are other examples of good writing in the resources for Sit Experiment 1: Read with Intention.

Better

The first book I read by him has the simple title, Better. It’s all about how we, as humans, can strive to do whatever we do better. I learned about positive deviance from him, that is, the way people like Jerry and Monica Sternim seek out and learn from people within a system who are already doing things better. Whose children in this village are the healthiest? What are they eating? Which departments in our hospital already have a high incidence of handwashing? How do they remember? He ends with five simple things anyone can do to get better at whatever they do. You won’t be surprised that the one I remember most clearly is his 4th point, quoted below:

“Write something— When you write something, it helps you step back and think through a problem. With the degree of thoughtfulness that you put into writing you eventually become a better person.”

I wrote a review of this book and its relevance to people practicing positive psychology in 2008, so my admiration has lasted a long time.

The Checklist Manifesto

In The Checklist Manifesto, Gawande starts by reaching for ways that medicine can excel by taking ideas from other high stakes operations. Pilots and copilots go through checklists before they take off to make sure everything is ready and operating correctly. They don’t check just what comes to mind. They use a written list as a memory extender. It might be my age, but I increasingly appreciate memory extenders.

As a physician, Gawande learned about checklists when he was looking for ways to reduce human error in medicine, the kinds of mistakes that come from ineptitude rather than lack of knowledge. One of the items on his surgical checklist is making sure people on the team know each other’s names. With changing schedules and personnel, that surprisingly simple item makes a big difference, particularly for tense moments when people need to work together with exquisite smoothness.

In my mind’s ear, I can hear my checklist-prone husband preparing to go to work years ago, “Wallet, watch, keys, badge, change.” In more complex situations, the checklist is always written down, and gone through with the entire team. Any complex human operation can benefit from people going through a checklist together before proceeding.

Being Mortal

Being Mortal addresses the question, “how people might live successfully all the way to their very end.” He ends the introduction, “And what if there are better approaches, right in front of our eyes, waiting to be recognized?” Here he is, applying the lessons he learned with Better in an extremely important arena.

Why do I admire him so much?

- He exemplifies vast competence combined with both humility and confidence. He doesn’t overstate. He doesn’t overquote others. He acknowledges what he doesn’t know. He is open to learning as he goes along.

- His writing is easy for me to understand even though I have never been to medical school. I imagine that he has explained medical topics to non-medical listeners for many years. Avoiding jargon, he knows what, when, how, and how much to explain with full respect for the needs and abilities of intelligent lay people.

- His stories make his wisdom come alive. He shows as well as tells.

- He repeats just enough and summarizes deftly so that a reader can build up a mental picture of the structure of his argument. I’m not overwhelmed by too many takeaways. In Better, he ends with a list of actions to do better. In Being Mortal, the chapter titles are a map for the journey.

Conclusion

Many of the people in my workshops are writing books that they hope will make other people’s lives better. I can think of no better model than the writing of this generous, honorable, and humble person who clearly lives what he writes. He faces today’s challenges with a strong hope that we can do and be better. His books are on my resource list for Sit Experiment 1 about how to improve writing by reading.